News / Press

Whitehot Magazine, "The Nexus Between Art and Science: Growing a New Naturalism", October 2024

[article excerpt]

Cosmology including relativistic and quantum mechanics, as well as the mysticism of Taoist philosophy mediated by a Japanese aesthetic, have both influenced Sandra Lerner’s worldview. Pervading her art is the idea that the universe is an inseparable reality enfolding an interrelationship of all things. Also nurturing her paintings are her love of color and her visceral connection with paint’s texture plus her sensitivity to the nexus between music and visual art. All these things coalesce in her “Entanglement” paintings, which explore cosmic consequences flowing from the utterly enigmatic entanglement between subatomic particles.

» View article

Lamina Project, FOCUS NEW YORK 2024

Article features work by Sandra Lerner

» View article

Interalia Magazine, "Exploring Oneness"

Article featuring Sandra Lerner

» View article

Art & Antiques, “Cosmic Connection”, March 2023

Feature article on Entanglement exhibition, Spring 2023

» View article

Panel Discussion, “Cosmic Aesthetics: Sandra Lerner’s Paintings” With Donald Kuspit, And Jeno Sokoloski

Moderated by Donald Kuspit, art historian, with Jeno Sokoloski, astrophysicist, Columbia University, and Sandra Lerner, painter, at the June Kelly Gallery, SoHo, NY, October 26, 2019

Dr. Donald Kuspit is one of the most prestigious art critics in the United States. A specialist in modern and contemporary art, philosophy, and psychoanalysis. Kuspit is Distinguishes Professor Emeritus of Art History and Philosophy at Stony Brook University and winner of the Frank Jewett Mather Award for for Distinction in Art Criticism, awarded by the College Art Association. He is the author of numerous books, catalogue essays and articles. Dr. Kuspit received a PhD in philosophy from the University of Frankfurt, Germany, a PhD in art history from the University of Michigan, and training in psychoanalysis at the Psychoanalytic Institute of New York University Medical Center.

Dr. Jeno Sokoloski is the Director for Science at the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope Corporation (LSST Corp) Before joining LSST Corp. she served as the President of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. After obtaining an undergraduate degree in physics from MIT, she moved to Japan to analyze X-ray observations of active galaxies. Completed graduate studies at Princeton and U.C. Berkeley, Dr. Sokoloski held a NSF Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Currently at Columbia University, where she has led an active research program on eruptive and interacting binary stars since 2006.

Sandra Lerner lives and works in New York City. Lerner has participated in many one-person and group exhibitions throughout the United States and Japan. She is represented in numerous public and private collections, including Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, Connecticut; Heckscher Museum, Huntington, New York; Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ; Kampo Museum, Kyoto, Japan; World Study Museum, Fukuoka, Japan; Price Waterhouse, and 3M Corporation.

The Feminine Cosmos: Sandra Lerner’s Sublime Paintings

by Donald Kuspit

How to represent the unrepresentable—the sublime, the sense of being in the presence of “unrepresentable excess” or “limitlessness”—that’s the task of Sandra Lerner’s paintings. They are undoubtedly abstract—they belong to the tradition of so-called musical painting that began with Kandinsky’s abstractions. But they are also representations of limitless cosmic space, grounded in a scientific understanding of its complexity--Lerner knows her astrophysics--not to say absurdity, at least to everyday understanding. In Lerner’s Macrocosm series, 2019, the circular, spinning disk-like shapes, radiating particles of light—cosmic radiation, energizing space, as it were--are wormholes, she tells us. But they may also be black holes, as Macrocosm VII, suggests. In Macrocosm I, II, and III they appear in the lower left corner of the painting, sending out a beam of light from a white-hot luminous core embedded in a red hot shape, sometimes circular, sometimes elliptical. The core is surrounded by an auratic ring of enormous circles that extend beyond the canvas, as though to convey the infinite space in which the explosive core—it resembles a volcano blowing its top, viewed from a telescopic distance— exists.

In Macrocosm I the aura dissolves into a darkish-bluish space, in Macrocosm III cosmic radiation spreads like an open fan: cosmic geometry and cosmic radiation—form and energy--are inseparable. In Macrocosm IV three cosmic forms, each with a luminous center embedded in a red aura, radiate— generate--rays of light. Is it too much of an imaginative leap to suggest that they resemble the sprouts of plants, implying that the cosmos is alive, germinates life—organically, certainly inherently, creative? More often, as Macrocosm V, VI, VIII, IX, X show, the cosmic forms are paired, as though magnetically attracted to each other, and interacting, as though in intercourse, I dare to speculatively suggest. It’s a no doubt all too imaginative over-interpretation, but one that I will argue makes unconscious sense--has emotional credibility--for however cosmic the content of Lerner’s paintings they are expressive masterpieces, indeed, ingeniously original abstract expressionist paintings. Their source is as much Lerner’s unconscious, as her acknowledgement of their psychological import--and indebtedness to Taoist philosophy, with its distinction between Yin and Yang (dark and bright, negative and positive, the receptive and the active principles), complementary opposites--as her scientific knowledge. The emphasis on pairing, doubleness, the attraction of opposites—the inseparability of opposites, resembling each other yet in separate spaces of their own, passionately drawn to each other in a desire for intimacy, as the surge and exchange of energy between them suggests, for the light that binds them is libidinous—is explicit in every work in the Macrocosm series. The cosmic pair holds its own in the infinite darkness, linked together by inextinguishable light.

Even more speculatively—and perhaps absurdly—I want to suggest that Lerner’s wormholes or blackholes are the hiding places, as it were, of the so-called Deus Absconditus, the hidden God that created the cosmos. Cosmic radiation is the basic subject matter of Lerner’s paintings, and cosmic radiation is inherently numinous. Looking at the night sky, with its radiant stars, one cannot help being awestruck by the mystery of the cosmos. I suggest that Lerner is a mystic in scientific disguise—or is it a scientist in mystical disguise: her cosmic paintings are scientific and mystical at once. They suggest that scientific knowledge of the cosmos can lead to a mystical experience of it—a sense that it is a “mysterium tremendum” (tremendous mystery or mysteriously tremendous) and with that peculiarly sacred.1

Does God inhabit the wormhole or blackhole—is God a wormhole or blackhole? Or is each a different manifestation of God? A wormhole is “a bridge or tunnel that provides a shortcut from one region of the universe to another.”2 Isn’t God a creative transitional shortcut between non-being and being, as the Book of Genesis, with its story of the creation of the cosmos, strongly suggests? God brings light out of the darkness—to find and see the light in the darkness is to see God. But God is also a blackhole, for everything light—everything brought to life by light—sooner or later falls back into darkness, dies in darkness. A blackhole is a symbol of Death: “a space-time warp...so radical that anything, including light, that gets too close to [it] will be unable to escape its gravitational grip.”3 I am arguing that Lerner’s paintings have subliminal existential as well as overt scientific and mystical import. Even more, they are subtly feminist, for they imply that God is feminine rather than masculine: God is creative, and women are inherently creative, for they possess a fertile womb. It is like a wormhole, for it is a transitional space between nonbeing and being, and like a blackhole, for there is no light in the womb. It remains dark as death until the one large egg it contains is fertilized by one small sperm. The many others that attempt and fail to penetrate the egg die in the womb. Lerner’s wormholes—symbolic wombs-- radiate raw heat. They burn brightly, a veritably inextinguishable fire,4 in stark contrast to the phallic pillar of cloud—little more than glorified smoke-- in which the male God appeared in the desert. I am arguing that Lerner’s wormholes and blackholes are the feminine sublime5 in symbolic disguise. And I am arguing that there’s more to Lerner’s paintings than meets the eye, however much they excite it: to view them only as exquisite illustrations of a scientific idea is to be blind to their visionary complexity-- their appeal to the mind’s eye, their multidimensional subtlety, their sublimity. They are full of wonder, but also wisdom.

Science and art converge in Lerner’s paintings, as they do in Kandinsky’s—he used science to justify his turn to abstraction, as his remark that “the theory of moving electricity, which is supposed to completely replace matter”6 indicates—but his knowledge of science was superficial compared to Lerner’s, as her Macrocosm paintings make clear. They convincingly picture the theory of quantum entanglement. It “occurs when pairs or groups of particles are generated, interact, or share spatial proximity in ways such that the quantum state of each particle cannot be described independently of the state of the other, even when the particles are separated by a large distance.”7 Quantum entanglement is cosmic dialectic: the interacting, interrelated, intertwined globular cosmoses, each with a dazzling white core surrounded by a pulsing yellow ring, in Lerner’s Microcosm series exemplify it. She looks down on her Microcosms, like a farseeing goddess on the heights of Olympus. She comes closer to her Macrocosms—in Macrocosm VII she daringly stares into the black hole. As though into the blind eye of a Cyclops? Is she provoking it, as Odysseus did? She is clearly on an odyssey in cosmic space.

Quantum entanglement is a theory of relationship: to say that one particle cannot be described independently of the other is to say that they are permanently in relationship and cannot exist without the other. Similarly, the wormhole’s regions of space-time remain connected—bound to each other— however widely separated. This particle is not thinkable without that particle, this region of space-time is not thinkable without that region of space. However far apart the particles and regions of space-time they’re together. They’re enigmatically equivalent to each other. Quantum entanglement theory and the wormhole are about cosmic relationships. I think they are metaphors for human relationships for Lerner. Like Yin and Yang, they form what psychoanalysts call a relational matrix. In the last analysis Lerner’s paintings are about the cosmic import of human relationships.

Notes

1 As Rudolph Otto, The Idea of the Holy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), 13 writes, “mysterium denotes that which is hidden and esoteric, that which is beyond conception or understanding, extraordinary and unfamiliar”—the tremendum. It brings with it a sense of the “uncanny” and “aweful,”

and with them a sense of “exaltedness and sublimity,” and finally of “absolute overpoweringness.” Otto calls this the “’urgency’ or ‘energy’ of the numinous object” (23), in Lerner’s art the cosmos. The numinous object brings with it a sense of “the wholly other”—wholly other than ordinary experience.

(29)

2 Brian Greene, The Elegant Universe (New York: Random House, 2000), 264

3 Ibid., 79, 81

4 Describing how cosmic radiation is created, Greene, 81 writes: “as dust and gas from the outer layers of nearby ordinary stars fall toward the event horizon of a black hole, they are accelerated to nearly the speed of light. At such speeds, friction within the maelstrom of downward swirling material generates an enormous amount of heat, causing the dust mixture to ‘glow,’ giving off ordinary visible light and X rays. Since this radiation is produced just outside the event horizon, it can escape the black hole and travel through space to be observed and studied directly.” Lerner’s paintings are exquisitely incisive renderings of the creation of cosmic radiation.

5 The feminine sublime is a concept developed by Barbara Freeman in The Feminine Sublime: Gender and Excess in Woman’s Fiction (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1995) to distinguish woman’s creativity from man’s creativity, conveyed by the concept of the masculine sublime. Freeman argues that the concept of the sublime, as it was developed by male philosophers, particularly Kant, unconsciously conveys the sense of what it means to be a man. Thus the masculine sublime is an expression of phallocentrism and with that an assertion of male narcissism and autonomy—absolute difference from woman, implying that a man can make art without being inspired by her: the sublime masculine artist does not need a muse to be creative. In contrast, the feminine sublime is an expression of womb-centrism and with that an assertion of female narcissism and autonomy—absolute difference from man, implying that a woman does not need a male mentor to be creative.

Freeman’s concept of the feminine sublime and Otto’s idea of the numinous object clearly coincide. Lerner’s feminine cosmos is a numinously sublime object.

6 Wassily Kandinsky, ”On the Spiritual in Art and Painting in Particular,” Complete Writings on Art (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 142

7Greene, 143

Art & Antiques, October 2019, Physics For Poets

Harvard Exhibition

Creative Flux Paintings

April 1 - May 4, 2017

Harvard University

Gutman Gallery, Graduate School of Education

Cambridge, MA

(Unveiling of Lerner’s painting, "Event Horizon", Harvard University Collection, November 8, 2017)

The Harvard Crimson, "Arts Asks: Sandra Lerner" Interview

by Nicole T. Sturgis

April 11, 2017

Sandra Lerner is a painter based in New York whose work explores the intersections between Eastern philosophy and theories in physics and cosmology. Her work is featured in collections around the world, including the Kampo Museum in Kyoto and

the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Connecticut. Currently, ten of her

paintings are on display in the Gutman Gallery, at Harvard’s Graduate School of

Education. This exhibit, “Creative Flux,” takes as its theme visual representations of Taoism and modern physics.

The Harvard Crimson: When did you discover Taoism?

Sandra Lerner: In the sixties, I went to a gallery opening that was selling these books on Taoism, and I read a passage by Lao Tzu from the “Tao Te Ching”.

“Look, it cannot be seen-it is beyond form -

Listen, it cannot be heard-it is beyond sound.-

Grasp, it cannot be held- it is intangible.-

These three are indefinable,

Therefore they are joined in one.”

“Stand before it and there is no beginning.

Follow it and there is no end.

Stay with the ancient Tao,

Move with the present.”

I discovered this in the midst of the human potential movement, and I became very interested in Taoism, Buddhism, and eastern philosophy. Then in the mid-sixties, I read Lawrence LeShan’s book, ‘The Medium, the Mystic, and the Physicist.’ I was thunderstruck by the similarities with physics and what they were proving and theorizing, which was so similar to what the Eastern mystics have been experiencing for thousands of years—that in the universe everything is interconnected, interdependent, and molecules on the smallest level [are] creating, annihilating, co-creating again.

THC: How have your trips to Japan and elsewhere in Asia influenced your art?

SL: I’ve travelled through Asia and been to Japan many times. I studied calligraphy with a master calligrapher there. This calligrapher in Japan sort of adopted me as a daughter, and I spent a total of eight months there studying with him, and I was an honored guest.

THC: How would you describe the paintings in this show?

SL: So what I do in my paintings is I use the dichotomies, which would be hard edges and the morphosis shape. For example, the line from the mountains where the softness of the background … seeps into this, and I have a framework for this, and it loops forward in the same way that Randall suggests that gravity is seeping in from a different universe. And also it could be that when we look at the sky, our eye is a frame, since we can’t see the whole universe in the same way astronomers look at the universe through a telescope. For me the lines thrusting outwards, using the hard edge with the texture and juxtaposing all the polarities in the paintings, is something that has really informed my work.

THC: Are the pictures meant to evoke landscape scenes?

SL: I try to suggest shapes. And many times these shapes to me look like mountains. It could be rivers, it could be lakes. And I just suggest, because I want the viewer to finish the rest of the story. And in this, I did feel the wave, because particles change into waves and waves change back into particles. Everywhere I am thinking about particles in flux and nature in flux as we are constantly evolving.

THC: What do you hope that the Harvard community takes away from your show?

SL: I really just want them to feel the work, and I think that with my work it’s not

just a matter of thinking, it’s a matter of pondering. I just suggest things, but I also want someone to look and see what the calligraphy means and draw their own conclusions. So it’s something that the viewer participates in. I have had collectors say to me years after they bought paintings, every time we look at it, at different stages in our lives, it means different things, and it seems to evolve as they evolve.

The Pythians, Sandra Lerner: Lyrical Abstract Paintings, November 2017

Sandra Lerner’s paintings originate in music. Trained as a concert pianist, she employs variations of colors and shapes that recall the transposition of musical chords and repetitions. In addition to music, her paintings combine Eastern tradition influences and postwar American art and Abstract Expressionism, creating a unique composition of spatial scope of lyrical expressionism.

Woman's Art Journal, Fall/Winter 2016, Vol. 37, No. 2

Sandra Lerner

The Particle and the Wave: Metaphysical Landscapes, Taoism, and the Calligraphic Impulse

by Aliza Edleman

Sandra Lerner is the subject of an in-depth article, The Particle and the Wave: Sandra Lerner's Metaphysical Landscapes, Taoism, and the Calligraphic Impulse in the Fall/Winter 2016 issue of the "Woman's Art Journal." The article was written by Aliza Edelman and published under the auspices of Rutgers University's department of Art History. The editors are Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow.

"Woman's Art Journal" is a feminist art history journal that focuses on women in the visual arts and serves as a forum for critical analysis of contemporary art issues as they relate to the women's art movement and art worldwide.

Donald Kuspit: Creative Flux in Sandra Lerner's Paintings

Exhibition Essay

June Kelly Gallery, October - November 2015

Looking at Sandra Lerner's new series of paintings, Flux/Space, one sees sweep,energy, subtle grandeur, and a hint of landscape. The painterly horizon line moving, with the insistence of what Kandinsky called "inner necessity," across the canvas, is sometimes dense and forceful, at other times seems fragile and uncertain, and always sky blue, so that it stands out of the atmospheric field it divides. The field is warmly yellow, as though flooded with midday light, sometimes tinted red. In some works small rectangles, sometimes bluish, more often bright red, appear in the field, like sudden revelations, unexpected perceptual epiphanies. The horizon line in Flux/Space 3 and 8 is broken: a continuum of fragments, so that it seems to stop and start, as though uncertain of its destination. In Flux/Space 9 and 10 the blue horizon line becomes a mountain range, vigorously painted with calligraphic gestures spontaneously appearing in the sky - the spontaneous gestures that the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott famously called the true self in action. As with the geometric forms, the expressionistic gestures have revelatory force - signs in the sky with ineffable meaning. The dramatic flurry of blue gesture in the lower section of Flux/Space 11 shows Lerner at her most intense. Lerner is a romantic visionary - her paintings seem rooted in the grand tradition of romantic landscape paintings, with the landscape reduced to its abstract fundamentals, streamlined to its expressive essentials. But the insistence of the horizon's movement - however changing shape, or suggestive of landscape, or a pure gesture dynamically equilibrated with pure geometry (the poles of abstraction playfully together while maintaining their difference) - suggests that something more is at stake than romantically suggestive pure art.

Lerner's line is in perpetual movement -- endless flux, a flux that can be read as spatiotemporal, a flux out of which time and space precipitate to form a natural world (Lerner's landscape), but also a flux in which it dissolves, as though nature was merely incidental to its manifestness, beside the point of its sheer givenness. In some of Lerner's works the lines seems seductive, even voluptuous, evoking the female body, or corporeality as such, which is what the mountains do. In others it seems agitated and tense, as though a nerve at loose ends. Sometimes it seems to move fast, at other times slowly; sometimes it seems taut, at other times slack; sometimes it seems labored, at other times it flows effortlessly. Whatever its expressive effect and momentum, and whether it signifies the horizon or exists for its own pure abstract sake, Lerner's line is inevitable, unstoppable, constant. I want to suggest that it is more metaphysical than physical: it is emblematic of what the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead calls "creative flux," for him "the category of the ultimate." For him "creativity is the universal of universals": whatever particular mood it conveys, whether it seems impassioned or serene, Lerner's line signifies universal creativity.

What Whitehead calls creative flux is what in Chinese thought is called the Tao. It signifies "way" or "path," or, more to the point of Lerner's paintings, "river": Lerner's horizon line is also a river flowing through a landscape - and pointing toward and going into the beyond, the vast sublime space of her open sky and broad field of her painting, and finally beyond it. The Tao is "a force that flows through every living and sentient object as well as through the entire universe. It signifies the primordial essence or fundamental nature of the universe." It is an endless process of continuous becoming -- a constantly ongoing creative process. Lerner is a student of Taoism; her paintings are Taoist in spirit, indeed, ambitiously Taoist: the Tao is "eternally nameless - not a name for a thing," which is why the grand horizontal gesture that cuts across her canvas can be ambiguously read as a horizon or river, or simply a purely abstract expression. Lerner's fluid line is as much a natural phenomenon as an aesthetic thing in itself, but above all it is an epitomizing expression of the Tao that informs both.

Art historically speaking, Lerner's paintings have a certain climactic place in the modernist tradition of what has been called Lyric Abstract Expressionism, as distinct from what I want to call Epic Abstract Expressionism. The difference is crucial for understanding the experience Lerner's paintings afford. Epic Abstract Expressionism is known for its painterly energy, not to say violence: the term "Abstract Expressionism" first appeared in 1919 in Der Sturm, which is why it is typically associated with Sturm und Drang (storm and stress, more pointedly emotional turmoil and upheaval). In contrast, Lyric Abstract Expressionism eschewed the violence and impulsiveness of Epic Abstract Expressionism for a more subtle, reflective, less reckless handling of painting. Both are species of so-called Action or Process Painting, but the "action" of the Epic kind is wild (some say chaotic, at best loosely structured, structure a tentative, unstable, improvised epiphenomenon of the "loose"paint handling) - thus the so-called "Neue Wilden" of the eighties - while the "action" in the Lyric kind is more focused and purposive. It is the difference between the peculiar coarse, flamboyantly explosive handling of paint by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline, and the more refined, intimate, studied handling of Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski and Mark Tobey. And it is the difference between the need to express the distraught, restless self and the need to assert something more fundamental than the self.

What makes Lerner distinctive in the tradition of Lyric Abstract Expressionism is that she instantly grasps this more fundamental thing, this vital current in all things, including the self - the Tao that is the source of its creativity. She articulates the ineffable Tao with ecstatic concentration - which is what I think her hyper-fluid yet self-contained line is. It has form, and form is structure, and the Tao has geometric form - sometimes geometric structure in the making, as its more idiosyncratic, fragmented appearance in some of Lerner's paintings suggests, sometimes structures as a seamlessly continuous form. Geometrical form is crystallized Tao, making its presence explicit. The self-contained geometrical forms that hover in the sky above Lerner's cosmic landscape epitomize this transcendental presence. Lerner is an ecstatic mystic, her whole being in touch with the Tao through the medium of paint.

A note: Lerner is an educated painter, majoring in philosophy when in college, afterwards studying Taoism, Buddhism, and physics. She was taken with Larry LeShan's book The Medium, the Mystic, and the Physicist and Fritjof Capra's book The Tao of Physics. It is important to know this, for it strongly suggests that an artist has to have knowledge - certainly serious awareness - of what is deeper than art, if she or he is to make an art that affords insight into inescapable truths, however much it also pleases the eye, affording aesthetic satisfaction. Lerner's paintings do both.

© 2015 Donald Kuspit

» View Creative Flux paintings

Parallel Universes 2010

June Kelly Gallery, New York

A very physical, very energetic and very direct interpretation of Japanese calligraphy became part of Sandra Lerner's painting approach at an early point in her career. Now, in a new body of work she further explores calligraphy's potential by combining vigorous gestural marks with evocative fields of subtle color. It is an approach that seems to heighten the bold power of the configuration. It also calls attention to the way Lerner investigates calligraphy's expressive force rather than its traditional cognitive associations. The brushes designed for calligraphy are important to her work, however, for they hold a substantial amount of pigment and allow the development of both heavy and thin marks with no interruption to the primary creative gesture.

The gestures deliver a spirited spontaneity and freshness. Intentionally, and in an edgy way, this contrasts with the textured, stone-like thick impasto surface of sand, grit and collaged materials that imply a geological continuum with an ancient, storied past. The sensed weight and substance expands the types of physicality present in each work. In addition, there are paintings embellished with marble dust that produce a mysterious luminosity. Some surfaces hold ghost-like echo images with characteristics of loose stains ("Wind Song") or structural elements ("Wave"), introducing more visual richness as they activate space.

The dominant, highly charged calligraphic shapes appear to be floating above the crusty surface, adding to the complex spatial experience. This strengthens the feeling that Lerner's painting approach makes otherworldly discoveries possible, and further underscores the validity of her continuing investigations.

© 2010 Phyllis Braff, New York

» View Parallel Universes paintings

Mona Molarsky, ARTnews, December 2010

Parallel Universes, June Kelly Gallery, New York

Sandra Lerner's recent paintings are not things to be viewed from afar. You need to step up closed and shift from side to side to see the textures and changing colors. Like ancient walls, their surfaces are complex and mesmerizing. Stretches of terra-cotta turn to carnelian and flame, Indigo canvases reveal their weave. Pale earth tones that conjure Sahara sands go golden and suddenly glitter. When the light hits it just so, Lerner's large canvas Sunshower (2010) sparkles as if infused with mica.

Using Japanese calligraphy as a starting point, Lerner often paints graceful black scribbles that suggest ideograms. Splashed, streaked, and dabbed, the expressive gestures give her planes a sense of depth and movement. In Autumn Mist (2010) a coppery field is covered with a blue-green, white, and red patina that establishes areas of energy. Small but sharply focused black brushstrokes look like letters from an unfamiliar alphabet. Chi Light (2010) features much larger shapes painted in an inky blue, suggesting Chinese characters smudged by rain. Even the title of the beigy pink Whisper (2010) implies a communicative impulse, albeit one that is buried in the whirls and squiggles of paint. Most intriguing of all was the big and searing Alternate Realities (2010). With its vertical format, brick-red hues, and faint grid-like design, the work evokes a wooden door. In the center, two vermilion circles seem to burn like rings of fire.

© 2010 Mona Molarsky

» View Parallel Universes paintings

Jean O'Neill, Citizen News, September 29, 2010

Parallel Universes, June Kelly Gallery, New York City

Life, the Universe and Candlewood Lake: The exploration of those forces are strong factors in the paintings of Sherman's Sandra Lerner, who splits her time between the expansive views from her Candlewood Lake home and her studio/home in Manhattan close to New York Union Square.

Sandra opens her latest show, Parallel Universes at the June Kelly Gallery, 166 Mercer Street, New York on October 7th and runs through November 9th. This series of new paintings is touched by many things including Sandra's extended studies of philosophy, painting and her thoughts on physics and cosmology, that's where Candlewood Lake comes in. "I have always been looking at the similarities between the spiritual and eastern philosophy and cosmology and physics," said Sandra from the perch of her comfortable deck where the views of Candlewood Lake, its islands and beyond go for miles. "The essence of this lake has been something that has informed my work for all these years," she added.

Sandra and her husband Kurt were married in 1985 and were based out of Manhattan. They began looking for a country home a few years later and a visit to a friend in Sherman quickly narrowed their search. They have been spending summers and long weekends here since 1991 and the differences from the Flatiron district where they live in the city and the breathtaking views of Candlewood Lake are found in Sandra's latest show and go back to her early works which were heavily influenced by her study of calligraphy with esteemed teacher Soshi Kampo Harada.

"I had always loved calligraphy," said Sandra who took a six week course studying the art in New York in 1970 with world renowned Kampo. At a post-class gathering at the United Nations, Kampo invited Sandra to visit and study with him in Japan. "He was a great teacher, and was really thought of as a national treasure and I was honored," explained Sandra.

It would be just over ten years before Sandra would take Kampo up on his invitation. "In 1980 I was being shown at the Betty Parson Gallery (whose gallery specialized in abstract expressionism - and had represented Jackson Pollock), and sold a painting I really didn't want to sell," said Sandra. However, that sale allowed her to put into motion a series of events that would let her take the Japanese master up on his invitation and bring her to Kyoto, Japan where her three week stay turned into four months and her studies of calligraphy and its intricate brushwork at Japan's ultimate calligraphy school would lead her back to Japan several times where Sandra exhibited at the Tokyo Museum in 1984, the Fukuoka Museum in 1985 as well as a return in 1993 for the schools' 40th anniversary. "Never in my wildest dreams did I see that coming," she reflected. "I was treated so well and am still close with Kampo's son and daughter-in-law."

"There's really so much work that goes into a painting that went into previous paintings that didn't work; and then suddenly it flows," explained Sandra who is well disciplined in the studio by 10am and working well into the evening. "I try not to let myself get sidetracked," said the prolific artist who has consistently been shown since the 1960s.

Her works tend to be in series, which include: Parallel Universes, Mystical Realms, Breath, Particle Physics and Mist. Sometimes the works she cuts from her initial un-stretched canvases will find their way to a show together. "I find that when I'm working on a series of paintings it's as though there's a dialogue between them. While it's a completely different search for each, they are somehow genetically connected," reflected Sandra who has long been fascinated by the connections of the spiritual and sciences. Her interest in the string theory, which suggests that everything in the universe is made up of vibrating, sub-atomic and string-like particles, takes into account that there are 11 dimensions rather than four. "It's about nature and relating to the universe," said Sandra about her paintings. "Taken from an intellectual, emotional and mystical view, string theory has evolved to include particle theory and M (membrane) theories which are very much a part of the Cosmos and relate to scientific Collision theory and the belief in Hindu philosophy that new universes are constantly being born. Combining the science and the spiritual is really me saying they are one and the same," she added.

The mojo of her work at times also incorporates calligraphy as a starting off point. "When I lectured in Japan they didn't understand why my calligraphic strokes didn't mean or say something. When we studied calligraphy in Japan our goal was to copy the master completely and the artistic statement was found in how the brush touched the paper. My calligraphy doesn't 'say' anything; it's a gestural approach to allow you to put yourself into the work and figure out what it says to you."

Sandra has participated in many one-person and group exhibitions throughout the United States, Europe and Japan. She is represented in numerous public and private collections including the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, Connecticut; Hecksher Museum, Huntington, New York; Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ; Kampo Museum, Kyoto, Japan; and the World Study Museum, Fukuoka, Japan; Price Waterhouse and 3M Corporation. She has also created sets for performances by Eiko and Koma, the acclaimed Japanese avant-garde modern dancers and choreographers. Sandra Lerner is represented by the June Kelly Gallery in New York City where she has been exhibiting since 1990 and has had six one person shows there.

"So much of life is serendipitous and being open to what happens," said Sandra who counts herself as lucky. Her friendly and inquisitive outlook and hard work give us the opportunity to consider how the views and sights and sounds of a lake so near and dear to our hearts can become tangible when mixed with the noise of taxi cabs and trucks outside of an artist's studio. Add to that years of travel, study and success and you'll see that Sandra's view of those parallel universes we all live in touch very close to home.

© 2010 June O'Neill

» View Parallel Universes paintings

Donald Kuspit, catalogue essay, Mystic Realms

June Kelly Gallery, 2004

Sandra Lerner: Mystic Realms

Sandra Lerner's paintings are inspired by "M" theory—and Mark Rothko. The "M" is the three-dimensional membrane on which our universe supposedly grows, according to string theory. One of its developers, the physicist Ed Witten, asserts that "M" means "mystery, matrix or magic." One can read this to mean that the membrane is the ultimate mystery, or, as the title of one of Lerner's paintings says, the Ultimate Reality, that is, the reality out of which our more ordinary contingent reality develops. For it is the membrane covering a multi-dimensional space—the so-called "bulk"—in which there are parallel universes. In other words, the membrane is the matrix that magically generates—or, as I prefer to say, mystically, for it is beyond conventional understanding—every possible universe.

What has this got to do with Rothko? Rothko famously declared in 1943 that he and Adolph Gottlieb "wish to reassert the picture plane," because "flat forms...destroy illusion and reveal truth." Rothko's flat planes are membranes floating in infinite space, each with a certain material density—a colorful bulk, as it were—of its own. The picture plane is, in effect, one membrane in the process of differentiating into—generating, spawning—many universes. They are parallel planes, so to speak, that meet in the infinity of the original (originating) membrane, as their discreet yet subtly intermingling colors suggest. From Lerner's point of view, Rothko's ingenious, oddly labored flatness reveals "M" truth. His paintings are abstract allegories of membrane theory. They afford, however unwittingly, insight into "timeless" truth, to use Rothko's own word, as distinct from the temporal illusions available to sight. Rothko's membranes confirm the romantic view that the artist's unconscious "anticipates" ideas that come into their own in science

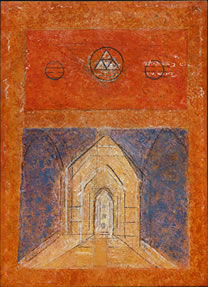

Now the artistically original thing that Lerner does is to geometrically delimit Rothko's planes into isolated individualistic units, bringing them into sharp focus (without disturbing their inner expressionistic life), and nail them down on the more "universal" membrane of the picture plane, also delimited—by the painting's edge, reflected in a ghostly inner edge. Rothko's planes tend to be open, formless, and improvised, rather than closed, fixed, and planned. Lerner not only stabilizes them, but they stand out in relief from the larger picture plane—technically, they are papier collés (literally rice paper) brought to painterly life—making their membrane character explicit. Like "M" theory, Rothko's paintings are about the creative process as such; Lerner's paintings bring it to its inevitable and logical conclusion: the steady emergence of definite, crystal-clear form—epitomized by Lerner's luminous temple-like structure—from indefinite formless energy. This centralized—and self-centering—sacred space symbolizes the autonomous universe or finished realm that develops within and emerges from the membrane-matrix. It also embodies the architectonic self-containment of each painting, suggesting their "self"-referential character: they symbolize the development of Lerner's "higher" consciousness—epiphanic awareness of the eternal membrane—out of turbulent amorphous unconsciousness, evident in the collaged dynamic planes.

The tension between the two, and their odd reciprocity—in Enlightenment the temple's triangular apex reappears in the small luminous triangle in the dark blue heaven above—suggests a dialectic of consciousness. The higher and lower planes of consciousness are opposed, but blue and orange mingle in the higher plane, suggesting that it is ready to bear fruit: the seminal triangle becomes a mystical structure. It seems to be a slippery illusion, but it is instantly evocative: the viewer can emotionally enter and identify with it, becoming as "enlightened" as it. They too can acquire an aura, confirming that they have "seen the light." Thus a sacred structure descends from the infinite membrane, bringing the eternal creative process down to earth with no loss of its sublimity. (Lerner's paintings remind us of the importance of aura and aesthetics, indicating that they cannot be extinguished by reproduction. Aura confirms the achievement of higher consciousness—as in the rays of light that emanate from Moses's head at the moment of his illumination—as distinct from the "dark," levelling, mechanical character of everyday consciousness.)

Lerner's Mystic Realms are clearly spiritual in import—like "M" theory. Like Hindu cosmogony, it argues for an infinite number of universes. Like all spiritual theory, her vision focuses on the reversible transformation of immaterial light and dark matter, that is, the communication/communion between contradictory realms of being and consciousness, implying their inner unity. Super string theory holds that all happenings arise from the vibrations of microscopically tiny loops of vibrating energy deep within matter. We see them in Lerner's Regeneration and Causation. One grand loop is apotheosized in Non-Being. Membranes and Strings makes Lerner's concern with string theory explicit. The strings are either open-ended and tied to the membrane, forming matter and light, or closed loops, for example, gravity waves, which may communicate with other universes. Both types of string are visible in Lerner's paintings. It is important to note that in the theory what seems abstract is profoundly concrete—like Lerner's paintings, which are abstract in form and symbol, yet deeply concrete, as their rich texture makes clear. From the perspective of string theory, our universe is a symphonic continuum ranging from sub-atomic particles to galaxies, each a different vibrating pattern of strings. Lerner's paintings seem to freely range across the continuum, spontaneously shifting from the sub-atomic to the cosmic while integrating them.

For me, her most "moving" realms are Remembrance, Mystic Spiral, and Resonance, for they seem simultaneously integrative and disintegrative. It is hard to say whether the arch in Remembrance is collapsing or rising. Are we witnessing creation or destruction, construction or deconstruction? Indeed, the arch seems to be collapsing in the act of rising—ready to fall to earth the more it yearns for heaven. The uncertainty continues into Mystic Spiral: the structure is not quite resolved—the apex is not reached, so that the arch remains incomplete—however much it vibrates intensely in space. The opposing curves converge in Resonance—touch but then separate. The arch as a whole is blurred however persistent—simultaneously in and out of focus—as though its materialization remained in question. It is determinate and indeterminate at once, suggesting concentration and diffusion of consciousness, as though its apex could never be reached however close it seemed. The arch is a "peak experience," but the peak seems to dissolve in front of our eyes, so that the experience remains equivocal. The arch's red "arms" stretch into the blue sky—the contrast is both poignant and stark—as though they could at last connect there. But they never do. It is as though they are raised in a gesture of futility; the arch seems to be asking for help from the sacred powers above. It is the entrance to the beyond, but it is charged with the amorphousness of the beyond itself, making consciousness of the infinite hard to sustain. We are in the presence of the unfathomable, which invariably evokes absence.

But the architectural structure becomes decisive in the other paintings, however much it remains in developmental process, as though it was the embryo of a cosmic enigma. Become a building, the arch loses structural ambiguity — its tendency to entropic collapse. The over-all geometry and atmosphere of Lerner's paintings — their tightly closed planes, sacred architecture, and subtle luminosity and intense energy, just as indwelling — suggests their meditative character. Clearly the central sacred structure — symbolizing the spiritual aspiration of the painting as a whole — is a meditative device. Lerner repeats it like the sacred syllable "om," inducing a similar exalted, transcendent state of mind. Her paintings convey this altered consciousness even as they "demonstrate" the process of alteration. They remind us that there is more than one kind of consciousness, just as string theory reminds us that there is more than one universe. Lerner shows that abstract art as well as theoretical science can be a way of contemplating and representing this unrepresentable timeless truth.

© 2004 Donald Kuspit

» View Mystic Realms paintings

Ken Johnson, Art Guide review, The New York Times, April 8, 2004

Galleries: SoHo

Sandra Lerner, “Mystical Realms,” June Kelly Gallery, 591 Broadway, near Houston Street, (212) 226-1660, through April 20. A painter who had her first New York solo show in 1969 presents easel-size paintings marked by crusty surfaces, confectionery color and Rothkoesque light. The symmetrical compositions are punctuated by transcendentally suggestive symbols (Johnson).

© 2004 Ken Johnson, The New York Times

» View Mystic Realms paintings

Amy Mulvihill, The Litchfield County Times

Mystic Realms, April 9, 2004

SHERMAN - Abstract artist and part-time Sherman resident, Sandra Lerner, says the works in her latest show were inspired by the twin muses of string theory and Sherman, Connecticut.

If you had a dime for every time your heard that one, right?

Cutting-Edge Theory

While some might be startled at such a strange juxtaposition of inspirations—string theory being the cutting-edge theory that everything in the universe is made up of vibrating, sub-atomic, string-like particles and Sherman, Connecticut being, well, Sherman Connecticut—Ms. Lerner sees nothing strange about it. In fact, according to her, it's not an unlikely pairing at all.

"It's all about nature and how I feel about relating to the universe," Ms. Lerner says about her artwork, which is on display in a show entitled "Mystical Realms" through April 20 at the June Kelly Gallery in Manhattan.

And of course, she adds, her interest in string theory and her Candlewood lakeside home in Sherman inform that relationship.

"From an intellectual point of view, an emotional point of view and a mystical point of view [string theory] is something that really grabs my imagination," Ms. Lerner says, referencing aspects of the theory that assert the existence of 11 dimensions rather than the concept of four.

"I've always felt that we have powers that go beyond the senses that we use in everyday life. I feel that there is another level that we are a part of," she states.

Ms. Lerner notes that this belief led her to study Eastern philosophies like Buddhism for much of her life but with the advances in particle physics and cosmology over the past few decades, science has ventured into territory usually reserved for religion and philosophy and Ms. Lerner has eagerly followed.

"Combining the science and the spiritual is really just me saying they're one and the same," she acknowledges.

This ethos is evident in her work which incorporates Rothko-esque color fields with calligraphic and architectonic iconography and texture-filled layers to achieve an effect that suggests the mystical, the religious, the secular and the infinite all in one.

For Ms. Lerner however, string theory isn't her only access to these ideas and the emotions they create. Sherman stirs similar metaphysical impulses.

Ms. Lerner and her husband, retired pathologist Kurt Gerstmann, settled in Sherman in 1991 after visiting some friends who had recently bought a house on Candlewood Lake. Ms. Lerner says she immediately fell in love with the area's topography and ambience.

"It was funny because I kept saying I wanted a place with an expansive view of water and mountains and sunsets, and my husband kept saying you're never going to find that within two hours of New York City," Ms. Lerner remembers, "and there it was all in one."

Ms. Lerner says the local New England architecture has informed her work with many of her latest designs drawing inspiration from local homes, barns and churches but that the inspiration she draws from Sherman is more all-encompassing than simply an aesthetic influence.

"My studio overlooks the lake. It's very pristine." Ms. Lerner begins slowly searching for the right words to describe the greater connection she feels Sherman facilitates between herself and the universe."One hardly sees any houses from the view and when I look at the reflection of the cosmos on the lake at night it is almost as if I can see the particles in the universe vibrating. I just find it very mystical," she concludes.

© 2004

Amy Mulvihill

» View Mystic Realms paintings

Cynthia Nadelman, catalogue essay

Sandra Lerner: Empty and Full

Sandra Lerner deftly synthesizes a variety of interests and influences. She is an artist who has studied calligraphy with Japanese masters and who has personally adopted Taoism and the teachings of Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu. She embraces classic Abstract Expressionism's leanings toward Asian philosophical and esthetic precepts.

There are sections in her paintings that absolutely savor of Chinese landscape painting and of calligraphy. Sometimes an entire painting feels that way, sometimes it is one of her window-like rice paper collage elements that feels or looks that way.

Lerner begins a work by pouring and painting on immense unstretched canvases placed on the floor, Jackson Pollock-style. From these she cuts out sections that inspire her, on which she then begins the next stage of painting. Sometimes those initial and later layers contain such elements - in addition to paint - as sand and marble dust of varying coarseness and tone, which imbue the work with a combination of shine and translucency. Sometimes she pencils in grid-like patterns. These straight, geometrically arranged lines delicately echo the effects of the collaged boxes and windows in her more materially layered paintings. Both lines and boxes have a structuring effect on these otherwise free-flowing paintings.

The calligraphy itself, which looks very much like writing but is not, serves mainly as an expressive design element, a painterly passage. It can be reminiscent at once of such nature imagery as a bird in flight or a solitary reed. Or it can call to mind the combined impression of poetry and history in an inscription down the side of a Chinese painting. These dashing linear elements — full of controlled abandon — present a counterpoint to the orderliness of the grid-like structuring elements. All of these painting events occur almost subliminally, mediated by washes and textures that create the symphonic backdrops against which these solo outings take place.

What Lerner has created are paintings that anyone familiar with the language of Western abstraction will be able to grasp. They are richly layered, while retaining a marvelous sense of space — or "breath," the word she uses to title the individual works. She calls her show "Empty and Full," and that dichotomy is really what the works embody. They are full of knowledgeable painting strategies, yet also refreshingly "empty" able to breathe. They are full of color, yet almost neutral, pale or scrim-like in effect. They are replete with useful and interesting contradictions.

To turn to the most challenging of these - Lerner's mixture of West and East - her work invites the question: how Asian is it? One need simply think of a hypothetical non-Western artist who has mastered traditionally Western painting techniques. One looks for evidence of native traditions, instances where the two cultures meet or collide, some sign, be it ever so subtle, that the artist is aware of the contradictions and symbioses. Lerner projects just such an awareness. Her work has for some time exemplified what we might now call "post-regionalism," as mixing and borrowing of cultures takes place the world over. It is a breath of air.

© 1999 Cynthia Nadelman

» View Breath paintings

Ken Johnson, Art Guide review, The New York Times, Friday, December 24, 1999

Galleries: SoHo

Sandra Lerner, June Kelly, 591 Broadway, near Houston Street, (212) 226-1660 (through Jan. 4). Working on the floor on big expanses of raw canvas, Ms. Lerner combines traditional Chinese brushwork, Jackson Pollock's splatter, Helen Frankenthaler's staining and Agnes Martin's pencil lines to create pale, beige abstractions that are physically assertive yet spacious and delicate.

© 1999 Ken Johnson

» View Breath paintings

Valerie Gladstone, review, ARTnews, March 2000

Breath Series

Sandra Lerner's paintings seem to float in air like elusive clouds. Lerner achieves her quietly captivating effects by combining Eastern and Western influences. Having studied calligraphy with Japanese masters and adopted Taoism and the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu, she has also embraced many of the techniques of Abstract Expressionism. Lerner begins, Jackson Pollock-style, by pouring and painting on immense unstretched linen canvases placed on the floor. She then cuts out sections and starts painting on them, sometimes adding sand and dust to achieve shine and translucency. Delicate lines and boxes and markings that look like writing but are not interrupt the overall fluidity of her paintings.

Lerner aptly called this show "Empty and Full." Most of the six works, titled Breath, from I to VI, are fairly large (72 by 58 inches), and all are painted in muted neutral tones. They are full of detail—lines that give the illusion of being birds in flight, mountain ridges, streams—and yet they are spacious enough to allow viewers to dream. Breath VI, for example, commands attention with two smudged gray circles and a wavering line against a pale beige background, while wisps of color float like half-remembered thoughts.

© 2000 Valerie Gladstone

» View Breath paintings

Donald Kuspit, exhibition essay, Mist Series, 1992

June Kelly Gallery

March 13 - April 14, 1992

Sandra Lerner's Mist Series of abstract paintings are a departure for her. Her new orientation reflects a move from the city to the country and a fresh awareness of nature.

There is continuity between old and new: the new atmosphere is framed by a semblance of the old architecture and even seems a refinement of the texture visible in earlier paintings. But above all, the same sense of mysterious femininity pervades both old and new abstraction.

Lerner's Villa of the Mysteries, 1989, with its overall architectural character and lyric surface - at once smoldering and muted, as though suggestive of unrequited passion - makes the point explicitly. It is based on the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, more particularly the famous wall-painting of a Dionysian Mystery Cult, ca. 50 B.C., showing a number of women involved in what has been described as "a religious ceremony...some solemn and arcane ritual."

Lerner eliminates the epic figures, but retains the stage-like architectural framework, pared to it spatial essentials. Columnar devices, related to those used to divide the space in the Pompeii painting, become the central feature in each section of Lerner's painting, replacing the figures. It is as though Lerner has made their phallic statuesque-ness explicit. One could say that the figures have been repressed, but their essence expressed.

In any case, they have disappeared, leaving only a surface behind. Whether this is meant to be the original raw wall, with some preparatory markings for the fresco, or the peeling, illegible remains of the fresco itself, the important point is that the surface that appears in Lerner's abstract wall-like painting is as arcane and feminine in import as the Pompeii figures.

Indeed, it seems to distill their archaic femininity, in all its erotic violence. Lerner dispenses with obvious female appearances in order to articulate the complex inner reality of femininity - the strange feminine dynamic evident in the Pompeii women - with abstract directness.

That is, the mystery of feminine passion and power emanates from the surface of the painting as it does in such similar Lerner works as Byzantine Morning and Echoes, both 1989, and Omega, 1990. While the surface in these works become progressively encrusted and agitated, and the columnar device fragmented - its parts laid out as though in an anatomy lesson - the sense of the mysterious feminine energy of the surface remains. It is the basis for the atmosphere of Lerner's Mist Series, 1991.

In this new series, the gestural glyphs that appear in some of the earlier mystery paintings reappear as cosmic signs, and the surface loses its reddish cast to become blue and gray. The tone has become more solemn than infernal, and more arcane than ever.

Lerner has moved out of the Villa of the Mysteries, with its hothouse atmosphere, into the open space of nature, while retaining a sense of brooding mystery. The new works are more inward than ever, for all their responsiveness to nature. The moon has replaced the column as an architectural device - the former symbolizes a chaste female goddess, the latter the phallic woman, in effect the poles of female identity - and the stage has become cosmic, but the obsession with woman's inner life, is stronger than ever.

Lerner no longer looks to art for a clue to femininity, but finds it in nature herself. Her Mist abstractions articulate her feeling of reciprocity between her femaleness and that of nature.

The mist ostensibly rises from a lake, but in Lerner's paintings it exists as a meditative substance in its own right. It comes to possess the architecture completely - that is, the inner collage frames (rectangles similar in proportion to the outer frame) - as the development from Mist No. 1 to Mist No. 2 to Mist No. 5 indicates.

At first thin, the mist grows thicker and thicker. It becomes all encompassing, but never completely obliterates the geometry of the frames or of the moon. It is as though there is a struggle between formlessness and form, never to be resolved. It is this that generates the sense of mystery that pervades Lerner's Mist abstractions. Does woman have greater tolerance for formlessness than man? Is she closer to formlessness, by reason of her natural power to give birth? Is Lerner suggesting the enigmatic inner relationship between formlessness and form? Her Mist abstractions raise these questions, inseparable from the sense of feminine mystery and power.

In Mist No. 4, the circle of the moon is juxtaposed with a cabalistic, figure-like glyph, possibly a sign from the Hebrew alphabet, and in Mist No. 6 two moons, light and dark, are side by side in a dense, hyperactive field, one of Lerner's most painterly.

In these works, the collage layering is gone, allowing for an effect of greater spatial immediacy. There seems to be nothing between us and the cosmos, except the mist. But cosmic space takes the form of formless mist on earth. Immersed in the mist, we are in effect at sea in cosmic space. Mist is feminine: it is a kind of natural veil, and as such an archaic symbol of female mystery. Both mist and veil signify woman's "mystifying" nature, by reason of her inner connection to the mystery of creation. Lerner's abstract mist implies that the cosmos is inherently feminine. Her paintings are about the mystery of cosmic creation of basic forms, spontaneously generated in the feminine mist, as though crystallizations of it.

Harold Rosenberg once wrote that "art works are no longer needed by society as cult objects, as ornament, as commemoration of events or persons." But they are still needed to catalyze and commemorate self-reflection, to invoke a deep sense of self: they are ornamental objects of the modern cult of self. Above all, art can suggest the archaic aspects of the self. Lerner's abstract Mist paintings are self-reflections, and by extension reflections on the female self. More particularly, they remind us that femininity continues to have archaic meaning, despite our scientific enlightenment about it. That is why it is still moving.

© 1992 Donald Kuspit

» View Mist paintings

Donald Kuspit, Exhibition essay for "Sensibility of Transcendence"

June Kelly Gallery, March, 1990

Sandra Lerner's abstract paintings have a new tautness, a new concentration to them. Previously, they seemed almost entirely a matter of calligraphic gesture and tonal atmosphere, conveying a general sense of mystical measurelessness. They were contentedly ethereal, effortlessly enigmatic.

Now there is a new structural measure to them, an overt architectonics, placing gesture and tone under control, confining them, as it were, and suggestive of some opaque new power.

Previously, structure was incidental in Lerner's works, at most an occasion—a prop—for tone and gesture, existing in a halo effect, as aura. Thus in TAO II, 1980-81, the small vertical rectangle in the lower left quadrant functions hieroglyphically, but more importantly looks like a catalyst for the fluid dense blackness that simultaneously accents and threatens to engulf it. Textural fluidity was in general dominant in her works of the early 1980s.

Now in VILLA OF THE MYSTERIES, 1989, the dominant feature is the vertical rectangle, made even more conspicuous by being doubled, both rectangles being made further conspicuous by the collaged textural tissue that marks them. The most significant gestural and tonal accidents of spontaneity occur within these twin frames within the gestural and tonal by these structures accidents occur within these twin frames within the frame,the compounding of the inner frame making it all the more absolute as interior space.

Not that all the gestural and tonal action is bound by these structures, or that it is superimposed on them. On the contrary, the synthesis and simultaneity of structure and atmosphere are self-evident—but without the geometry it would seem all too incidental, will o' the wisp. With the simple geometric structure and the columnar elements that typically coincide with it, the atmosphere becomes site-specific, as it were, and more fraught with spiritual urgency.

Lerner, whose works are influenced by Oriental landscape, desires the same unity of material structure and immaterial atmosphere that exists in them—the same sense of the interpenetration of matter and spirit. But being modern, she wants it in abstract emblematic form, that is, in a completely "ideal" way. Her geometrical matter exists in and through her textural thick and thin, and vice versa, conveying an all-over sense of crystalline emanation. CHINESE GARDEN WINTER, 1988, makes the point clearly. The quasi-Kufic script—a precipitation of the gestural calligraphy, as it were—embodies the new concentration, the new intensification, for structure and atmospheric flow are transparently simultaneous.

In ECHOES and OMEGA, both 1989, the geometrical details seem especially crystalline, holding the intense atmosphere in suspension.Textures build up but never become unruly, over-expansive—never dissolve the various geometrical framing devices. In OMEGA, the central calligraphic gesture seems to be held in place—indeed, given its own self contained form—by the columns that flank it. such a specific and site specific gesture, so concentrated in on itself, would have been unthinkable for Lerner earlier in the decade. The sensibility of transcendence that has always informed her works has taken on a new definiteness, been given a fresh determination.

The hieroglyph of OMEGA concentrates in itself all the energy that was once diffused over the field of the painting. It is an insistent new affirmation of transcendence, now seemingly actualized in the hieroglyph, rather than simply a possibility of all-overness. The collage surfaces —a literalization of the gestural and tonal atmospherics—confirms this new concretization of transcendence. It is now no longer an idea haunting a field of painterly operations, but a reality actualized in form.

Yes, Lerner continues to be a Taoist, but there is a new edge to her Taoism.In her works of the early eighties, she seems to endorse the idea of water as the symbol—of Tao—of spiritual calm, which like water alternates between perfect tranquility and periodic motion. The fluidity in the early works was like oddly rippling water, full of uncanny energy that was implicitly seeking its level of calm. The surface seemed more calm than disturbed, seemed to be settling down rather than rolling up.

In these late eighties paintings there is less tranquility, however much the geometrical structures seem to meditate it. They seem a deliberate effort to impose calm, rather than inevitable in their calmness. The surface seems more disturbed than in the earlier paintings. The geometry may be fused with the surface, but its axiomatic simplicity seems an enforced tranquility rather than one that spontaneously emerges from the field, from the surface itself, as in the earlier works.

In the end, the atmospheric calligraphic surface and the formal geometry are subtly at odds, giving these works an especially uncanny feeling. Indeed, the surface of Lerner's late eighties works seem potentially violent, certainly aggressive, which was far from from the case in her early eighties work. There is a new tough-mindedness to these paintings.

Lerner has moved from lyric abstraction to epic abstraction, from spirituality that could be taken for granted to spirituality that has to be militantly affirmed. The new force in these works suggests that the infinite she is obsessed with has come down to earth. The sublime has been partially desublimated, become less ethereal, in the process of becoming more vigorous, assertive—active rather than passive.

This represents a strengthening rather than slackening or spiritual purpose. Now, transcendence is implied even while the materially realistic—explicit in the collage textures—is indisputably indicated. Lerner suggests that material itself has transcendent implications—that the sensibility of transcendence is not only a a matter of articulating a separate spiritual space, but can appear as sensual surface.

© 1990 Donald Kuspit

» View Transcendence paintings

Lowery Sims, exhibition essay, Inland Sea

Betty Parson's Gallery 1982

"There is a symbiotic relationship between the material object and the sounded one. They energize each other… tell their own story… turn each other on and the viewer with their suggestive and narrative powers." This quote from Loyd Herman's introduction for the exhibition catalog THE OBJECT AS POET evokes pertinent aspects to the work of Sandra Lerner. The relationship between the word and the image is indeed a frequent concern as she allows the words of the Chinese poet/philosopher, Lao Tzu, to guide to guide her working. The resoundingly tangible impact of the most subtle illusive haiku conveys the sense of the impact Sandra Lerner's work may have on the viewer.

Again, Herman: "The object provides thereness, a physical place: it holds the space, marks the terrain, the geography, the metaphors. The poem breathes and gives voice singing and chanting the metaphor of the image." Lerner's "object", the paintings, are the arena for a constantly alternating process of the creation and destruction, delibility and obscurity. She builds up the compositions bit by bit, melding various media and material, effecting multiple textures. Rice paper is torn, posted, pushed, wrinkled, well-torn; paint pigment brushed, sprayed, squiggles, thrown. Sand, gel medium and other material are joined in a vigorous yet tentative play upon the canvas. The results are ambiguous yet aura-ed presences.

Visually, Sandra Lerner's paintings harken to romances of ancient manuscripts with exuberant, elaborate calligraphic elements disposed upon the surface tracing the secrets of old writs which have somehow survives the ravages of time. Scrolls, tongas, Persian manuscripts float before our eyes eschewing the specific linguistics reference, but the scale allows the viewer to seek associations with larger-scaled cave paintings or temple decorations. The fact that most of her recent paintings - wall hanging - are smaller in scale and meant to be hung without stretchers enhances the personal devotional magical functions of the work. Like that of the gestural abstractionists of the last forty years, Lerner's calligraphy is non-referential to existing tautologies, and rather establishes her random transcriptions which can allude to music as well as literature. The calligraphy serves not only to enliven the canvas, but also to create an ethereal realm within which the many marks which the drama of the canvas occurs. Lerner manifests a contemporary interest in the integrity of each of the many marks which are accumulated on the surface of the canvas, as well as the more expansive obliteration of the surface with the pigment. Underlying the automatic, experimental, spontaneous, restrain, and to offer contrast within the overall visual message. A subtle, yet architectonic structure allows repletion with variation, sequence within progression, and rectlinearity within amorphousness.

Within the ‘architecture' and the ‘topographies' of the paintings we can discern spectral presences beckoning towards us through levels of the spatial and temporal planes. Two sometimes three of these entities may coincide, distinct yet identical, emerging to and from the surface of the canvas like images gradually evoked from a tomb rubbings. Relationships of the void and the mass established by the contours of the obscured areas left after the pigment has been sprayed and brushed on adjacent areas, establish evocative allusions about physical reality and illusion as set on the two-dimensional surface in painting.

It is the reconciliation of divergences and complimentary opposites in Lerner's work which point to her commitment to arrive at a perfect synthesis of eastern Eastern mysticism and Western tectonics, which will preserve and permit the integralness of each approach to life.

Lowery Sims

Assistant Curator, 20th Century Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

» View Inland Seas paintings

Inland Sea

Poetic illusionism is the term which has been used to describe Lerner's personal abstract expressionist style… (She) has been influence by eastern philosophies and mysticism as well as the most progressive artistic trends.

Thomas Hoving

(former director, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

» View Inland Sea paintings

Houston Museum of Fine Art, Houston, Texas, 1984

Tao Series, John Canaday

Sandra Lerner's, "Tao Series IV" is a beautiful painting that raises a serious of question. Seven-and-a-half feet high and ten feet wide, it exists as a single delicate area without dramatic accents, a subtly unified surface more like a page from a book, in spirit, than the wall-sized composition that is is, making use of collage, impasto, stains and semi-calligraphic squiggles against a background almost imperceptibly divided into rectangular sections. On either side, two large forms, like ghosts of the ancient trumpet-shaped Chinese bronze ritual vessel called ku, invest the painting with echoes of ceremonial functions. The tonal values are so close that they virtually disappear in a photograph: hence no illustration here.

The question is, what can you do with a painting of this size, if you aren't a museum and don't live in an enormous house? I know that one enthusiastic prospective purchaser went back to New York to check the dimensions of what he thought was the perfect spot in his study, and found the union impossible. Maybe, as one solution to the producer-consumer imbalance, painters who work in big, airy studios should contract into the dimensions of a New York apartment in order to develop a sense of salable scale.

May 9, 1976, John Canaday, New York Times

» Tao Series paintings